Why Traditional Psychology Gets It Wrong

For over a century, psychologists and philosophers have sought to classify the “basic desires” and drives that animate human beings. Influential frameworks—Reiss’s 16 Basic Desires, Self-Determination Theory, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, and the “Core Human Drives” model—have catalogued an impressive array of human motivations, from curiosity to altruism, from power to transcendence. But are these lists truly fundamental, or are they elaborate surface descriptions, missing a deeper, unifying root? This essay argues that nearly all human desires, even the most abstract or self-destructive, are ultimately elaborations of a single evolutionary drive: the demand for recognition.

The Flaws in Traditional Models

Across the history of psychology, several prominent models have attempted to describe the roots of human motivation by cataloguing so-called “basic desires” or psychological needs. Notable among these are Reiss’s 16 Basic Desires, Self-Determination Theory (SDT), Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, and the Core Human Drives model. While these frameworks have become deeply influential in research, education, and popular self-help, they share important structural weaknesses when examined from a neuroscientific and evolutionary perspective.

Reiss’s 16 Basic Desires

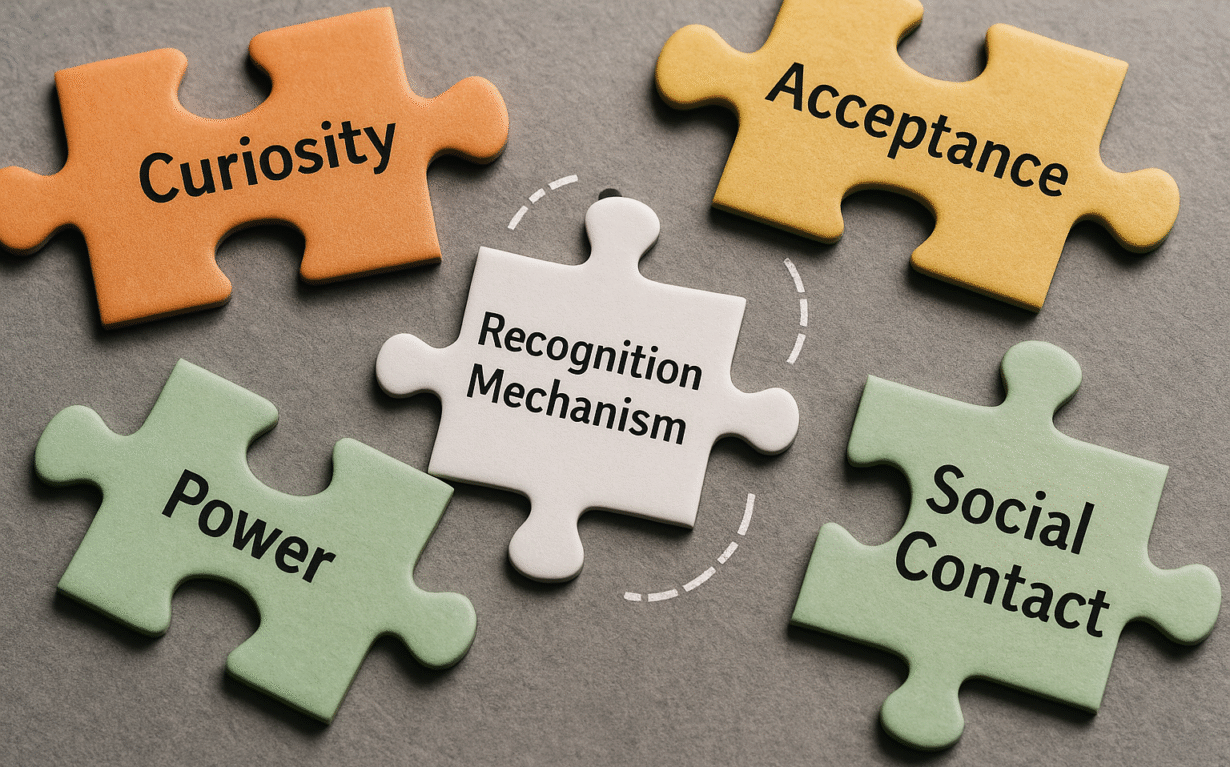

This model organizes human motivation into 16 distinct categories (e.g., acceptance, curiosity, honor, power, status, vengeance), each supposedly innate and fundamental. However, many of these “desires” overlap in content (e.g., status, power, and acceptance are all facets of social recognition), and several—such as honor or idealism—are heavily filtered through cultural norms, not universal biological imperatives.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

SDT posits three core psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. While this model is more parsimonious, it still treats these needs as separate motivational forces without probing whether they are themselves expressions of a deeper root mechanism—such as the demand for recognition or social belonging.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow’s famous pyramid orders needs from the physiological (food, water) through safety, love/belonging, esteem, to self-actualization and beyond. While intuitively appealing, this hierarchy is descriptive and culturally embedded. The boundaries between levels (e.g., between esteem and belonging) are blurry, and higher-level needs such as self-actualization or transcendence may be special cases of more fundamental drives, reframed as social recognition or self-validation.

Core Human Drives (Personal MBA)

This model distills motivation into four or five fundamental “drives”: to acquire, bond, learn, defend, and feel. Although it attempts to simplify the list, it still describes observed behavioral clusters rather than explaining their neural or evolutionary origins. For example, the drive to acquire (status, power) and the drive to bond are both deeply rooted in the demand for recognition within social groups.

Common Structural Weaknesses

- Arbitrary Segmentation: These models frequently divide overlapping behaviors into discrete “drives” without recognizing their common neural or social root.

- Cultural Contamination: Abstract or symbolic categories (e.g., honor, idealism) often reflect historical or social context more than evolutionary necessity.

- Surface-Level Taxonomy: The focus remains on what people do or claim to want, not why such patterns are universal or how they are wired into the mammalian brain.

- Lack of Reductionist Clarity: None of these frameworks sufficiently explain how and why so many “desires” converge on a single evolutionary function—such as securing social recognition, status, or belonging—critical for survival in hyper-social species like humans.

While these models offer practical tools for categorizing and discussing human motivation, they lack explanatory power at the level of neural circuitry and evolutionary function. They are, at best, maps of human desire—helpful, but not the underlying territory.

The Case for Recognition as a Fundamental Drive

Neural and Evolutionary Foundations

From a neuroscientific perspective, the brain is constantly monitoring both internal and external states, using a comparator mechanism to maintain equilibrium—physically, emotionally, and socially. In social mammals, survival is not simply about food or shelter, but about being seen and valued by the group. Recognition (positive social feedback, status, inclusion) is evolutionarily critical: it ensures protection, mating opportunities, and access to resources. Rejection or invisibility triggers the same neural pain circuits as physical harm.

Comfort and Mating: The Two Reductionist Roots

Eidoism argues that all motivation reduces to two basic evolutional needs: staying comfortable (homeostatic equilibrium) and mating (reproduction). While powerful, this reduction does not overlook how, in humans, the comfort zone is fundamentally an abstraction—neurologically manifested as a neural node or network representing both physical and social equilibrium. The brain’s internal “comfort-uncomfortable” comparator does not itself monitor states; rather, it functions purely as a mechanism for comparison. When an entity or association triggers this comparator—whether through physical sensations like hunger or through social cues like the risk of losing status—the resulting output determines whether an action is initiated to restore comfort or avoid discomfort. Only in this process, when comparison is activated by internal or external stimuli, do sequences of actions resembling monitoring arise. Thus, comfort in humans is not limited to bodily safety but extends to social and psychological balance, with the comparator acting as an abstract neural mechanism for evaluating deviations from equilibrium. Monitoring and behavioral responses are downstream consequences of these comparisons, all integrated within the same neural systems that govern our overall sense of well-being.

Recognition as the Underlying Thread in Multi-Level Motivation

This recognition-centric view provides a unifying explanation for a wide array of behaviors:

1. Multi-Layered and Emergent Motivation

Even highly abstract pursuits—creativity, meaning, self-actualization—are best understood as strategies for securing recognition, whether from others, from oneself, or from an imagined audience. Emergence in motivation does not require independence from this root drive; rather, complex motives are elaborations and extensions of recognition-seeking circuitry.

2. Altruism and Self-Transcendence

What appears as true altruism or self-sacrifice often involves a prediction of future recognition—social approval, legacy, or self-respect. Even anonymous good deeds are typically accompanied by internalized “observers” who grant the individual recognition, ensuring the neural rewards for such acts.

3. Cultural and Symbolic Needs

Cultural and symbolic motivations—national pride, religious devotion, artistic achievement—carry their force precisely because they offer membership, prestige, or validation within a group. Meaning and belonging are two sides of the recognition coin.

4. Delayed Gratification and Counter-Comfort Behaviors

The willingness to endure discomfort or delay gratification is a bet on future recognition—honor after sacrifice, mastery after discipline, social admiration after hardship.

5. Maladaptive and Self-Destructive Behaviors

Self-sabotage and self-harm are desperate strategies to manage negative recognition or avoid shame. More fundamentally, self-destructive behavior is often a loud scream for recognition: when more adaptive routes to positive acknowledgment fail, the mind seeks to force the world to “see” the individual’s suffering through dramatic or dangerous acts.

6. Recognition Beyond Comfort or Mating

Critically, the mind does not need actual recognition—the expectation or prediction of recognition is enough. The brain’s motivational systems are tuned not only to reality, but to anticipation and imagined feedback. Social pain and joy can be triggered by expected outcomes as powerfully as by real ones.

Recognition as the Core Loop

By re-examining classical and modern theories of motivation through the lens of recognition, we arrive at a simpler, more elegant model: The human mind is a recognition-seeking, prediction-driven system. All “basic desires” are ultimately strategies for securing positive recognition, avoiding negative feedback, or anticipating either. Even complex or self-defeating behaviors can be traced back to this core neural drive. While exceptions and nuances exist, the demand for recognition may be the root from which the tangled branches of human motivation grow.