Democracy or Autocracy: Structure Is Not the Point

Much of modern political theory and popular discourse focuses on the form of governance—democracy, autocracy, technocracy—as if it alone determines the quality and sustainability of a society. The assumption is simple: democracies are freer, fairer, and better for human well-being; autocracies are oppressive and unsustainable. But this assumption fails when measured against actual human outcomes.

Both types of systems can produce peace or collapse, prosperity or poverty. What truly drives system stability and elite success is not the structure, but how citizens are shaped—psychologically, economically, and culturally.

Performers vs. Contributors: The Functional Citizen

From the perspective of power and profit, the ideal citizen is not the wise contributor but the emotional performer. Performers are people who:

- Constantly seek validation and identity through visibility.

- Attach personal worth to public approval, likes, or social status.

- Consume to signal status.

- Follow trends and feedback cues from others.

These citizens are economically productive, politically passive, and psychologically dependent. They don’t question the deep structures of power, because their needs are met through symbolic approval loops: fashion, media, career titles, and self-branding.

In contrast, a contributor is dangerous:

- They reflect.

- They resist trends.

- They consume less.

- They seek structural meaning.

A system built on recognition does not need thinkers. It needs performers.

The Hidden Elite: Extraction Without Exposure

Both democratic and autocratic systems have elites—but in today’s world, the true power structures are rarely elected or visible. They exist in:

- Financial markets.

- Global corporate monopolies.

- Media conglomerates.

- Intergenerational wealth.

These entities extract value regardless of national borders or political forms. What they need from the masses is not participation, but compliance. And nothing guarantees compliance better than a recognition loop:

- People fight for attention, not power.

- People compete for symbolic status, not structural change.

- People consume endlessly, thinking it makes them free.

The elites don’t need to oppress—they simply feed the loop.

Democracy as a Recognition System

Democracy claims to be about voice and choice. But in its modern form, it has become a stage of endless symbolic performance:

- Politicians are brand managers.

- Citizens are divided into lifestyle identities.

- Elections are media spectacles.

- Justice is public outrage, not structural correction.

Democracy thrives on appearances. What matters is not the long-term structural good, but what gets applause in the moment. Media-driven feedback loops create a simulation of agency while preserving core hierarchies.

Even resistance is absorbed into the loop: protest becomes fashion, critique becomes content, and rebellion becomes monetized.

Autocracy and the Performer Class

Autocracies may use more centralized control and visible enforcement, but the psychology remains similar. Performers are rewarded through:

- Obedience and loyalty.

- Symbolic nationalism and identity.

- Controlled avenues for status: jobs, marriage, military, or culture.

As long as people feel seen—by the nation, the leader, the community—they often accept their material limits. The loop remains intact, even if dressed in different symbols.

Autocracy doesn’t need ideology. It needs ritual and spectacle.

Happiness as a Tool of Stability

One of the more subversive realizations is this: it doesn’t matter whether the happiness of the people is deep or false—as long as it is functional.

Happiness through consumption, distraction, symbolic recognition, or entertainment stabilizes the system. It lowers the need for change. It masks structural inequality. It makes injustice tolerable if it’s wrapped in dopamine.

The system—whether democratic or autocratic—only fears happiness that leads to clarity. That is: happiness that detaches from performance and exposes the loop.

Eidoism’s Perspective: The Loop Is the Real Ruler

From an Eidoist view, the central issue is not how leaders are selected, but how recognition is distributed:

- Are people constantly performing to be seen, accepted, admired?

- Are values defined by applause or structural necessity?

- Are roles structured around truth and contribution—or optics and hierarchy?

Even the best-intentioned system will fail if it does not address the loop of recognition at the core of human motivation. A structure cannot be free if the mind remains enslaved to symbolic validation.

Eidoism calls not for a new structure—but for a new psychology of form: a system where visibility loses value, and contribution gains meaning.

Governments Don’t Care If You Perform

The final irony is this: systems do not collapse because people are alienated. They endure because people are kept busy with symbolic performances. The illusion of freedom, the chase for visibility, the consumption of meaning—these are the tools of control.

Leaders, whether elected or self-appointed, are often interchangeable with performers themselves—sensitive to applause, desperate for legacy, bound to oligarchic influence. Real power is in the hands of those who understand the loop and use it.

Thus, Eidoism’s critique is not of democracy or autocracy per se, but of the psychological mechanism that both exploit: the demand for recognition.

Until that is broken, all structures serve the same master.

The Leader as Performer, the Oligarchy as Director

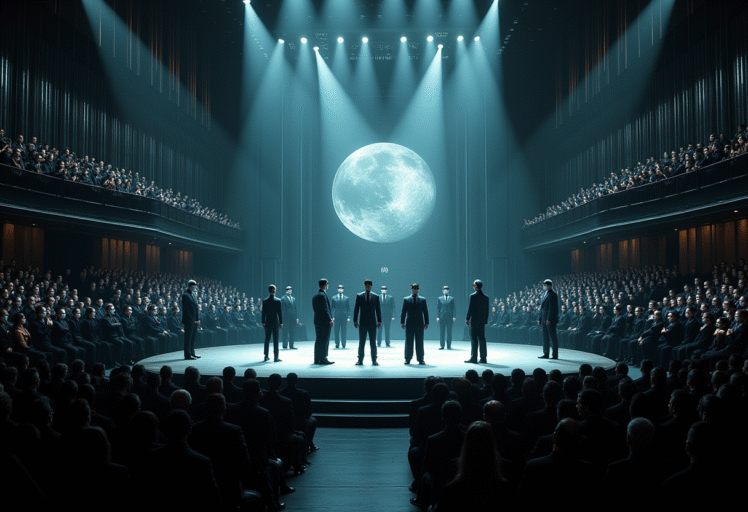

Political systems often elevate leaders to mythic status—heroic presidents, visionary monarchs, reformist strongmen. Public discourse and media culture amplify the idea of the singular leader as the engine of history. Yet when the veil is lifted, we find a very different reality. No leader ever governs alone. Behind every ruler stands a complex web of influence: advisors, financiers, generals, media owners, industrialists, and institutional elites. These actors do not merely support the leader—they define the limits of what that leader can do.

Leadership, then, is not an act of isolated power but a performance—carefully staged for public view, yet tightly choreographed by those who operate behind the scenes. While the leader occupies the spotlight, the true direction comes from the shadows.

The Performance of Legitimacy

To survive in power, every leader must play two simultaneous roles. First, they must satisfy the expectations of those who hold real structural influence—the oligarchic class. This includes maintaining access to capital, preserving institutional continuity, and avoiding disruption to elite interests. Second, they must appear to serve the people, embodying hope, unity, strength, or progress, depending on the mood of the time.

This dual performance creates a tension. Leaders campaign on promises of transformation, yet once in office, they often reinforce the very status quo they claimed to challenge. They speak in the language of reform while acting within the boundaries set by financial, legal, and military constraints. Far from being hypocritical, this contradiction is embedded in the very structure of leadership under modern governance.

Power That Doesn’t Need to Be Seen

What the public sees are elections, public speeches, scandals, press conferences, and symbolic gestures. But the true architecture of power remains deliberately invisible. It is found in wealth that transcends generations, in corporate-state alliances, in judicial appointments and central bank decisions, in informal networks that never appear on any ballot.

Leaders may change. Parties may rise and fall. Revolutions may promise something new. But the underlying power networks—those who control capital, information, and institutional leverage—remain largely untouched. These are not figureheads. They are the true custodians of continuity. And they do not need your attention, applause, or consent.

The Illusion of Political Agency

This understanding leads to a sobering conclusion: idolizing leaders is one of the most effective tools of distraction. It channels collective frustration or hope into individual personalities, making politics a spectacle rather than a structural force. The people are cast as an audience, urged to cheer or boo, while the script remains unchanged behind the curtain.

Eidoism invites us to see this for what it is: a loop of symbolic recognition. We admire, we protest, we vote, we react. But the deeper structures of control remain intact—because we never ask who builds the stage, who writes the lines, and who profits from the show continuing.

To break this cycle, it is not enough to replace one leader with another. We must step outside the loop altogether and begin designing a society where performance no longer defines power, and where form—not recognition—determines worth.